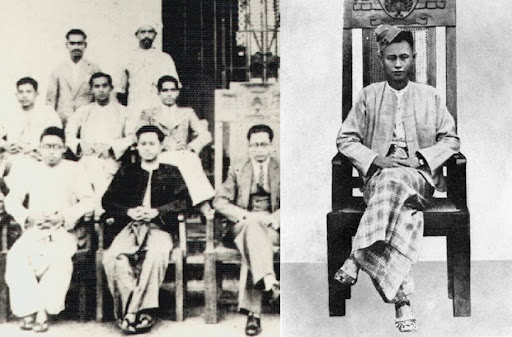

Left: Ko Aung San, seated second to left, in a portrait of the Oway magazine’s editorial committee (1936); Right:A portrait of Ko Aung San the President of the All Burma Students Union (1937)

It’s the nineteenth of July, 1947. Four months have gone by since the leaders of both Great Britain and Burma agreed upon terms for the inevitable independence of the latter, four months since the historic, legendary maybe even, Panglong Conference, and two months since the formation of the country’s first pre-independence Government. On what would become a fateful Saturday, however, an army jeep, carrying four men clad in full military attire armed with three Tommy guns, a Sten gun, grenades, and pistols, candidly drove, parked, and unloaded at around 10:30 AM into the courtyard of the Secretariat Building located in now downtown Yangon. After passing by multiple sentries posted to guard the building with little, if any, resistance whatsoever, the four men arrived on the third floor of the building, where, on that day, Burma’s pre-independence Government was holding a regular weekend cabinet meeting.

Killing the eighteen-year-old bodyguard watching over the council chamber, the four men quickly entered the meeting room, where they ordered that everyone remained still and seated. One man immediately stood up, nonetheless, provoking the four gunmen to begin mercilessly spraying the room with bullets for the next thirty seconds straight, eventually killing five of Myanmar’s forefathers and wounding three, who later on succumbed to their injuries, present at the meeting—thus, leaving none alive. We commemorate this day, the nineteenth of July, every year still, 78 years later, to these nine martyrs as Martyrs Day. This one man, however, who stood right up as his would-be assassins entered the room, whose memory, as citizens of Myanmar, to this day, we all remember and honour, was the one and only Bogyoke Aung San—the ဖခင်ကြီး, father, of our beautiful country.

Born on the thirteenth of February, 1915, when we think of this man today, of Bogyoke Aung San, we think of the man who won his country and its people their due independence—the man who rallied the masses around a single cause, independence, and fought for it relentlessly—the man who, by the end of his twenties, had made a name for himself at so young an age to become one of history’s most recognisable figures and the country’s most loved. What’s left out here in this portrait, however, is the most important—his portrait as just a person. We, the younger generation, and perhaps every other generation that has come after Bogyoke’s assassination, know little about him and who he really was—who he really was with family and friends behind closed doors. One might expect him, understandably, to have been a man with rather sharp manners and an honest appearance. Yet, surprisingly, such an assumption would actually land far from what was the case in reality. No, he was not at all like what most people today would presume him to have been like.

Untidy, rugged, angular, odd, and awkward were just a handful of the kinds of words many of his closest friends and family members used to describe him during his college years. As a student, and still long after that, Ko Aung San was known to be rather, say, bizarre. When he passed by his friends in the street, for instance, he would often do so without even a single word or gesture. His mood, it is said, alternated frequently between babble and silence. Depending on his frame of mind, “he could talk a listener to a stage of weariness or maintain an unapproachable and breakable silence.” If, however, despite this, we took a look at his other side, we would soon see that this was all merely just a front he chose to put up—with reason. There wasn’t any ounce of doubt in anyone’s mind that, behind it, he wasn’t anything but an admirable and sincere man. “He was highly respected by his generation of students, although some thought him” again “a bit eccentric.”

Straightforward in his mannerisms, thinking, and speech, one colleague of his described his words as often being stilted and short—framed in small bursts. He spoke loudly, putting great emphasis on each of his words with a “self-styled finality.” Usually, brutally frank. He walked in a manner more rapid than the average Burman and had a laugh that was “hearty, loud, and uninhibited.” Table manners were, lastly, unknown to him as well. However distasteful this all was for those around him, still, it was all for good reason. Idle things, such as these, could be dispensed with for real friendship, he believed. The act of friends opening “their hearts to each other, discussing, when need arose, freely and frankly” were of far more meaning for Ko Aung San. Far from being obstructionist and unsocial, he was, in reality, therefore instead, merely being “precise and realistic,” revealing something else about his character—something important.

There’s a well-known saying by the Greek Stoic Seneca that if one does not know to which port one is sailing, no wind can ever be favourable for him. It seems that from a very young age, Ko Aung San knew exactly which port he wanted his life to arrive at. “I would like to know English better,” he confided once to his friend, “and perhaps even take a shot at the examinations for the Indian Civil Service. After I had passed, I could then throw my job away, as Subhas Chandra Bose did, and go into politics. Then the country as well as the Government would look up to me for my education as well as my dedicated purpose.” On one famous occasion at a conference, Ko Aung San rose up to speak, putting on a show, prompting students around him to boo. Untroubled, he continued and spoke on. When a friend of his much later, who was also booing him then, reminded him of that time after Ko Aung San had become a much better speaker, he laughed and confessed that he would spend hours practising in his room shaping and developing his speaking skills. As just a student even, he was taking on the task of “learning the psychology of the masses [and] preparing himself for leadership,” his friend thought then. A singleness of purpose.

His achievements could never have been attained without one other essential ingredient, however—passion. “Politics was Thakin Aung San’s life, and lesser things such as hunger and discomfort did not matter.” Politics, it is said, was his sole existence. “Nothing else mattered for him. Not social obligations, not manners, not art, not music. Politics was a consuming passion with him, and it made him, I thought, crude, rude, and raw.” There would be times when he’d stay up all night, hard at work at his desk with a pen, reading, writing, drafting notices, resolutions, speeches, and reports, lost in thought. At dinner table discussions, his friends noted he’d always see discussions from a political angle. Politics was his life. The struggle for independence, similarly was his life. During his life, it was a popular fallacy that his political zeal was due to his ancestry to a famous anti-colonial revolutionary and royal. He hated this claim and often retorted that it arose instead from his own love for his country and, most importantly, of his people labouring under a repressive colonial ruler.

If there’s anything more crucial to a person’s success than an education, it’s, no doubt, the presence of role models in that person’s life—people who they can look up to, turn to for guidance in their stories, for wisdom, for counsel, direction. Sometimes, these role models come in the form of those most immediate to us, as in family members and friends. Sometimes, however, they come in the form of people who may not even be around anymore, like, say, for example, Ko Aung San. There indeed may have been aspects of his personality anyone at all would find repellent, which no one denies, but there existed aspects of his personality, too, far greater in number and weight that many around him found to be worthy of praise. Candour, purpose, and an untamed passion for his country and countrymen: by replicating and adapting these sterling qualities to their daily lives, Myanmar’s youth could do a huge favour not just for themselves and their future careers but, even more importantly, too, for Myanmar and its future.

Notes

The eight other fallen were as follows: Thakin Mya, then a minister without portfolio who was a close friend of Bogyoke, U Ba Choe, then minister of information, U Abdul Razak, a Tamil Muslim, then minister of education, U Ba Win, then minister of trade, Aung San’s older brother, Mahn Ba Khaing, then minister of industry, Sao San Htun, then minister of the Hill Regions and a Shan prince, U Ohn Maung, then a deputy minister in the ministry of transportation who was there that day simply to deliver a report, and the bodyguard, Ko Htwe.

Shine Lin Zay Yar

Virginia Tech

Bibliography

Aung San of Burma, edited by Maung Maung, Netherlands, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1962, pp. 7-28.

Leave a comment